Power At Work’s audience largely consists of people who are well educated about the labor movement. In our posts about Power At Work’s Quarterly Labor Issues Surveys, we describe the people who respond to the surveys as “labor insiders and knowledgeable outsiders.” That’s a fair description of most members of the Power At Work community. Yet, it is often those who are least educated about unions and worker power who would benefit from our content the most.

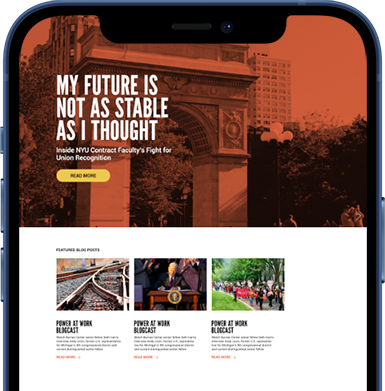

This new series, “Students & Solidarity,” is aimed at one of those groups: college students. It will be written by college students, for college students, and presented periodically over the course of the next several months. And it includes links to a long list of Power At Work posts, blogcasts, and podcasts that can provide additional information for those who want to learn more.

This is the inaugural article in the “Students & Solidarity” series, which we hope will make unions and the labor movement more understandable and more accessible to a younger audience, although readers of all ages are cordially invited to enjoy these posts, as well. Our experience on our college campus is that unions, although a powerful force in the United States, are often misunderstood by our classmates, or not understood at all. If we do it right, this series of posts will put a small dent in that problem.

It is critical that American workers — especially those who are privileged to have access to higher education and the good jobs it often gives us the opportunity to fill — understand unions and their benefits before entering the workforce. In addition, college students are playing a large role in the growth of unions on college and university campuses and beyond. We want their classmates to understand why this development benefits them, workers in higher education, and our country as a whole. And perhaps we can help to light a spark among some number of our readers to get involved in worker organizing and other forms of collective action.

Unions have a rich history in the United States, and are becoming more and more prevalent in the mainstream news. Presidential candidates Kamala Harris and Donald Trump have discussed them extensively in their campaigns.

In 2023, 16.2 million American workers were represented by a union. Roughly 10% of the country’s workers were union members in 2023. In the public sector, 32.5% of workers were union members. So, what is a union and why does it matter?

A labor union is a group of workers who join together to collectively advance common interests. In the workplace, those include wages, benefits, protections against unfair discipline and discrimination, work schedules, workplace safety and health, and much more. Outside the workplace, unions often represent their members in politics and lobby governments on their behalf to advance their interests. Unions may also engage in charitable and community activities, and often become social hubs and mutual support systems for their members.

A group of workers can form a union in multiple ways, but the effort virtually always begins with organizing. Organizing is little more than union organizers and workers who support the union talking with other workers in a workplace about their shared work-related issues and how a union might help them address those issues. This process usually begins quietly to avoid the employer intervening with anti-union campaigning early in the process. Once a sufficiently sizable number of workers have signed “authorization cards” declaring they want the union to represent them, the union and the workers may decide to take their organizing public.

It’s important to note that the right of private-sector and most federal government employees to organize is protected by federal law. Many states have laws protecting local and state government employees’ right to organize. That does not mean that employers will not violate the law to bust a union organizing drive. There are many legal ways for employers to oppose unions that are coercive, such as mandatory, closed-door anti-union meetings called “captive audience meetings.” Nonetheless, workers who believe their right to organize has been violated can file a complaint with a regional office of the NLRB and, if it is a valid complaint, the NLRB will prosecute it.

To learn more about organizing a union, watch or listen to Power At Work’s interview with Jaz Brisack, one of the founders of the first Starbucks Workers United union. You can find other perspectives by learning about the growing world of organizing in the nonprofit sector from Power At Work’s blogcast with two leaders of the Nonprofit Professional Employees Union. Yet another perspective can be found in Power At Work’s blogcast about AFSCME’s volunteer member organizing program.

Once the union has gained enough support, there are three ways to establish a union. The first formal option involves the workers who support the union requesting voluntary recognition from their employer. This option is available only if a majority of employees in the workplace have signed union authorization cards. The second formal option, if the employer does not voluntarily recognize the union (or the workers do not bother to ask because the answer will certainly be “no”), is available only if at least 30% of the employees have signed authorization cards: the workers who support the union file for a petition for an election with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), which is the federal government agency that administers and enforces our country’s private-sector labor law. If a majority of those who vote in the NLRB-administered election vote for the union, then the union will be certified by the NLRB. That’s one of the reasons why workers who want a union usually do not seek an election with only 30% support. They usually wait until they reach 60% support or more so their odds of winning the election are higher.

The third option is not formal and it is less commonly used, although it can be found in some industries and among some workers who do not have full collective bargaining rights. The workers may decide to establish a “members only union.” These unions are not the product of voluntary employer recognition or a NLRB election. Rather, they operate more like advocacy organizations for their members and other employees in their workplace and beyond. The employer is not obligated to bargain with them (see below), and there are other protections that are not available. Nonetheless, federal law protects most private-sector employees’ right “to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.” That’s what these members only unions do.

Some unions are experimenting with new ways of organizing that do not fit into these three neat categories. To learn more about one example, watch or listen to Power At Work’s blogcast with the leaders of the California Fast Food Workers Union.

Collective bargaining is the means by which those workers who have formally formed a union by following either of the paths above achieve the workplace improvements and power they seek. Collective bargaining is simply negotiations between the union and the union members’ employer about wages, working hours, benefits, and other working conditions. It is the process by which workers’ voices are heard in the employer’s decision-making about the issues that affect the workers most. It is also the process by which workers secure the benefits of having organized a union. Some topics, like wages and hours are “mandatory subjects of bargaining,” which means both sides must agree to discuss them. Other topics are “permissive subjects of bargaining,” which means the parties can choose to discuss them or not.

If successful, these negotiations are supposed to result in a collective bargaining agreement (CBA), which is signed by the union and the employer. Collective bargaining can be a difficult process and there is no guarantee of success. Particularly when a union is new, employers may try to slow down negotiations to frustrate their employees and deprive them of the benefits of organizing a union. Federal law requires private-sector employees to bargain in good faith with their employees’ unions. Of course, they do not all obey that provision of law.

If an agreement cannot be reached, employees may choose to go on strike. This can also happen when one agreement expires and the next one is being negotiated. A strike is when employees choose not to work until they receive the offer that they desire. Recent examples of strikes in the US include the United Auto Workers strike at Stellantis and the Longshoremen strike representing East Coast and Gulf Coast dockworkers. The inverse of a strike is a “lockout.” During a lockout, management refuses to allow employees to work as a way of putting pressure on workers and their union to reach an agreement.

There were 452 total strikes called in the United States in 2023. Those strikes involved over half a million workers. Two-thirds of those strikes ended within a week, while fewer than 5% of strikes in 2023 lasted longer than two months. To learn more about 2023 strike activity and where strikes took place in the country, watch or listen to Power At Work’s interview with Johnnie Kallas where he discusses Cornell University’s Labor Action Tracker.

Once in place, simply put, unions are very effective in helping the workers they represent. In 2023, union workers made a weekly median earning 14% greater than non-unionized workers’ earnings. Union members are also more likely to have employer-provided health and retirement benefits.

Unions are also rapidly growing in popularity among the American public. A Gallup poll found that 71% of Americans approved of labor unions in 2022, which was the highest mark since 1965. So far in 2024, that approval rating sits at 70%. In a time when much of the political discourse in the US is centered around wealth inequality, unions are looked upon as an avenue to help workers. These trends have aligned with growing support for unions among young people. Millennials and Gen Z are especially pro-union.

Organizers are also getting more and more successful at forming unions. Over the last four years, workers seeking unions have drastically improved their win rates in NLRB-administered union representation elections, thus leading to thousands more union members in the US.

Still, unions will continue to face challenges. Union busting – actions taken by employers to weaken or destroy unions or to prevent unionizing in the first place – is ever present in the American workforce. To learn more about dealing with union busting, read longtime organizer Phil Cohen’s article on Power At Work.

As unions grow in popularity and are discussed more and more, it is imperative to stay educated, and to stay up to date. I encourage you to follow along with our “Students and Solidarity” series and to subscribe to Power At Work. We will send you our weekly newsletter. With the newsletter, you will receive relevant and compelling articles, a weekly blogcast (video and audio podcast), and the Weekly Download, which compiles news stories from the past week relating to unions, worker power, the labor movement, strikes, and more into one place for your convenience.